Among the most frequently asked questions regarding hair loss is, ‘will exercise prevent hair loss,’ or ‘does exercise cause hair loss?’ The answer isn’t so straightforward. There’s more than one type of hair loss, countless forms of exercise, and lots of variables at play when we look at the relationship between the two.

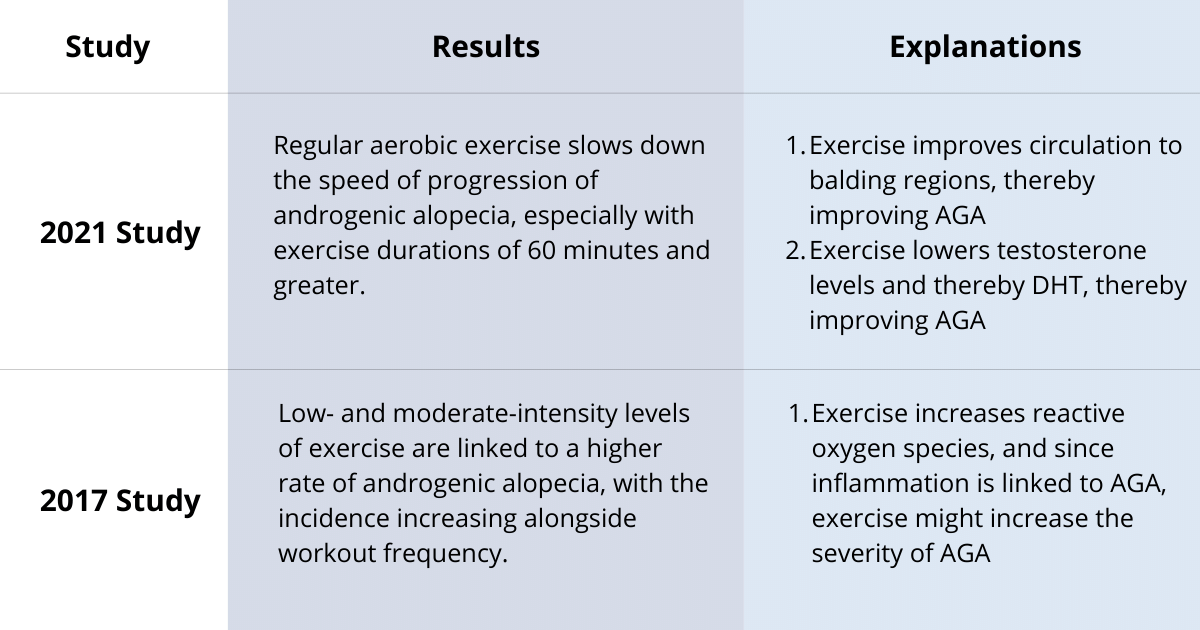

To tease out the nuances, we took a closer look at two studies focused on the correlation between exercise and hair loss. A 2021 study seems to correlate exercise, specifically long-duration aerobic exercise, with improvements in hair loss. The other, from 2017, seems to suggest that people with baldness are more likely to exercise.

These might sound contradictory, but the devil is in the details. By taking a closer look, we can learn something about exercise and hair loss (and also about cause and effect).

Key Takeaways

- The science on exercise and hair loss is mixed and studies often seem to conflict

- But subtleties in the questions asked and methods used tell a different story

- Recent research makes an effective case for the benefits of exercise

- Finally, we answer the question: Is there one best workout for hair growth?

About Exercise and Hair Growth

The science on exercise and hair loss has been mixed. There’s supporting evidence to show exercise is associated with hair loss. There’s also research linking certain exercise habits to hair growth.

So, which studies are right? Which studies are wrong? Or are all study findings on exercise and hair loss relevant – and it’s simply just the context of that research that influences its interpretation?

To find out, let’s build the best case for and against exercise and its possible link to hair loss. We’ll start with a recent study out of China.[1]https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34382589/

The case for exercise improving hair growth

(2021 Study) Does Exercise Influence the Progression of Androgenic Alopecia?

In 2021, a group of research dermatologists from Central South University, China sought to explore the relationship between exercise and the speed of progression of androgenic alopecia (AGA).

For background, androgenic alopecia is one of the world’s most common hair loss disorders. It’s chronic, progressive, and mainly driven by a combination of male hormones and genetics. It often presents as typical hairline recession and crown thinning in men and diffuse thinning in women.

Due to its high prevalence, androgenic alopecia is not only one of the best-studied hair loss disorders, it’s also the most likely diagnosis for adults noticing hair thinning. As such, when asking questions about exercise and its relationship to hair loss, studies on androgenic alopecia are of particular relevance.

Study Design

These researchers set up a study to answer one question: in the absence of any hair loss treatments, does exercise influence how fast androgenic alopecia will worsen?

They recruited 592 men and women who’d been diagnosed with androgenic alopecia in the prior year. None of the subjects sought any hair loss treatments for at least six months. All of them were in good health.

Six months after their appointment, the investigators sent participants a survey to collect information about their exercise habits since their diagnosis.

- How often were they exercising?

- For how long were they exercising?

- What kinds of exercise did they do on a weekly basis?

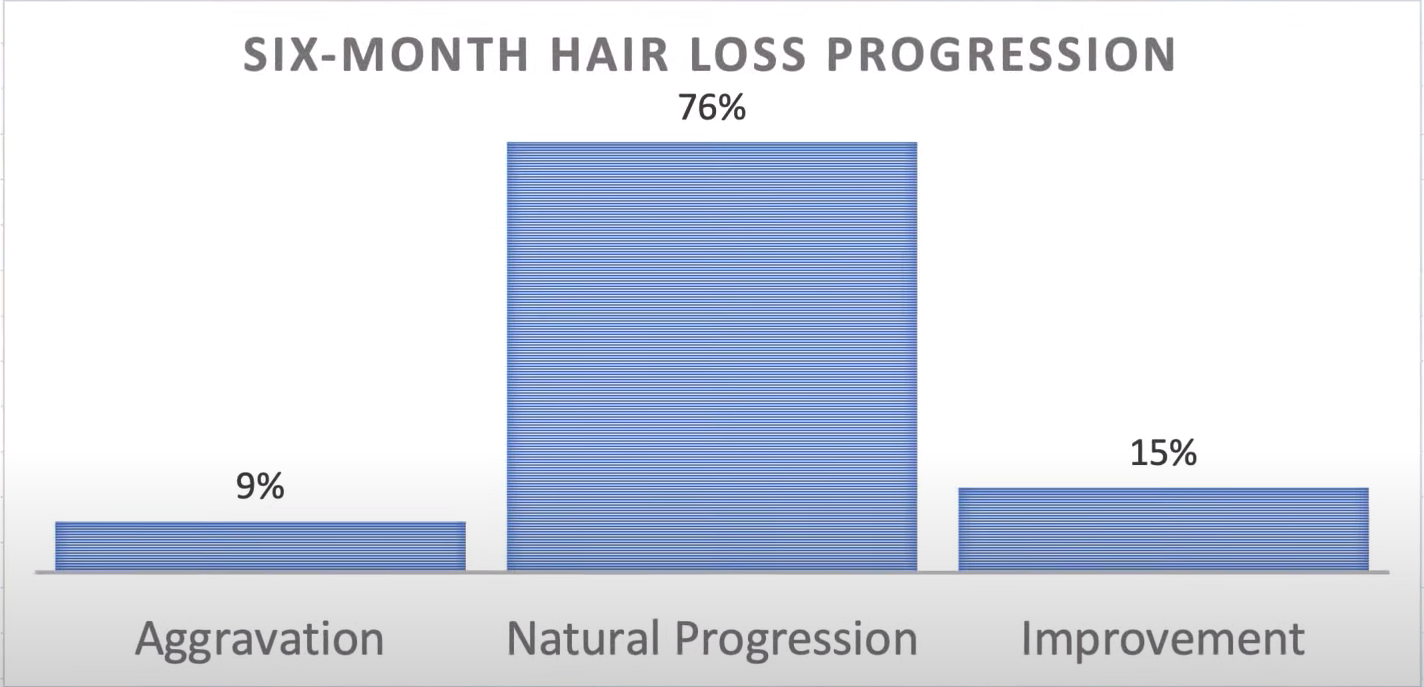

Then, using photographic assessments from the initial appointment and the 6-month follow-up period, both the investigators and the subjects assessed any changes to hair loss as one of the following:

- Aggravation – i.e., hair loss at a faster pace than usual

- Natural progression – i.e., hair loss at the same pace as usual

- Improvement – i.e., a cessation of hair loss and/or observable hair growth

Here are the results of the assessment – i.e., the results without controlling for exercise habits over the last six months.

Note: in the absence of treatment, men and women with androgenic alopecia typically lose 5% hair volume per year. As such, a 76% natural progression of androgenic alopecia is expected in any 6-month period, regardless of the introduction of new treatments, exercise habits, any other factors.

Finally, the researchers stratified these results by exercise type, frequency, and duration. The goal: to see if certain exercise types, habits, and/or frequencies were correlated with faster and/or slower rates of progression for androgenic alopecia.

So, what were the findings?

Study findings

Finding #1: Exercise was positively correlated with improvements to androgenic alopecia

Overall, the investigators found a positive correlation between improvements to androgenic alopecia and the frequency and duration of exercise. The more someone exercised, the more likely they were to report hair improvements over the six-month study window.

Finding #2: Aerobic exercise was linked to improvements for androgenic alopecia –and particularly for longer exercise durations

Interestingly, those who were doing aerobic exercises (such as cardio, jogging, or swimming) were 5.4-fold more likely to report hair improvements versus those who were just doing leisurely activities (i.e., yoga or hiking). Moreover, subjects exercising more than 60 minutes per workout saw better improvements than those working out for 30 minutes or less.

Finding #3: Shorter, more intense exercises were not associated with better (or worse) hair loss outcomes

High-intensity exercise in the form of sprinting, weight training, and/or interval training was not associated with improved rates of hair loss. But, importantly, these exercises also weren’t linked to a worsening of hair loss speeds. So, while these exercises didn’t help, they also didn’t hurt.

Moreover, these exercises appeared helpful to overall health in other ways. In fact, 46% of subjects who exercised reported improvements to depression and anxiety. So, while more intense exercise efforts did not have any perceived effects on the speed of pattern hair loss, all forms of exercise helped to improve the mood and well-being of participants.

Authors’ analysis

Why might some forms of exercise slow the rate of hair loss, while others do not?

Put another way: why were participants who regularly engaged in over 60 minutes of aerobic exercise 5.4-fold more likely to report improvements to hair loss over that six-month study window versus participants who only engaged in leisurely activities?

While we don’t yet have definitive answers on these findings (or what might explain them), the investigators offered two possible explanations.

Explanation #1: longer aerobic efforts might improve circulation to balding regions

Balding scalp regions tend to have 60% lower oxygen levels than non-balding regions. Moreover, research groups consistently observe that balding regions have relative microvascular insufficiencies (i.e., reduced blood flow). While a portion of these reductions to blood flow are considered consequences (rather than causes) of the balding process, there’s also some evidence to suggest that a portion of these reductions to blood flow occur prior to the balding process, and that targeting to improve blood flow might improve hair counts. This is why many vasodilator medications – minoxidil, diaoxide, and pinacidil (to name only a few) – have shown an ability to regrow hair lost to androgenic alopecia.

Interestingly, long-form aerobic exercises also improve circulation in the peripheries – such as the skin. As such, the authors argued that these exercises, when sustained long enough (i.e., > 60 minutes), might help improve circulation in balding regions that are hypoxic (i.e., lacking blood supply) – thereby increasing blood, oxygen, and nutrient transport to miniaturizing hair follicles and lengthening their hair cycles.

Explanation #2: longer aerobic efforts might lower circulating testosterone levels, and thereby slow the progression of androgen-mediated hair loss (like androgenic alopecia)

Evidence on marathon runners and ultra-endurance athletes show, over time, that long forms of exercise actually lower baseline testosterone levels. Interestingly, androgenic alopecia is a hair loss disorder that occurs, in part, due to a testosterone byproduct known as dihydrotestosterone (DHT).

For these reasons, the authors speculated that longer aerobic efforts might have also lower testosterone metabolites – like DHT – to a therapeutic degree (i.e., the slowing down of hair loss). This is an understandable argument, because effective hair loss drugs – like finasteride – also target to lower that very same hormone.

How far DHT levels can decline with exercise alone – and whether those declines will lead to positive effects on hair follicle miniaturization – is still very much up for debate.

Summary (so far): the case for exercise improving hair loss

A 2021 study from China found that men and women with androgenic alopecia who (1) regularly performed aerobic exercise, and (2) whose exercise durations were longer than 60 minutes were 5.4-fold more likely to report improvements to androgenic alopecia over a six-month window versus those doing any other form of exercises (or no exercise at all) – even in the absence of hair loss treatments.

The authors of this study speculated that these improvements might be due to the ability for aerobic exercise to (1) improve circulation to the peripheries – like the scalp – and (2) lower overall testosterone production, thereby reducing the hormones causally linked to the progression of androgenic alopecia.

It’s an interesting study, and with plausible points to explain the authors’ findings. So, does this mean that we should all start doing 60 or more minutes of aerobic exercise daily in hopes of improving hair growth?

Not so fast. We’ve only built one side of the argument. And this study’s findings do not necessarily agree with all other studies done on hair loss and exercise. So before we change our exercise routines in hopes of improving our hair, it is best to put this information into perspective.

The case against exercise improving hair growth

(2017 Study) Are Exercise Habits Correlated With Androgenic Alopecia?

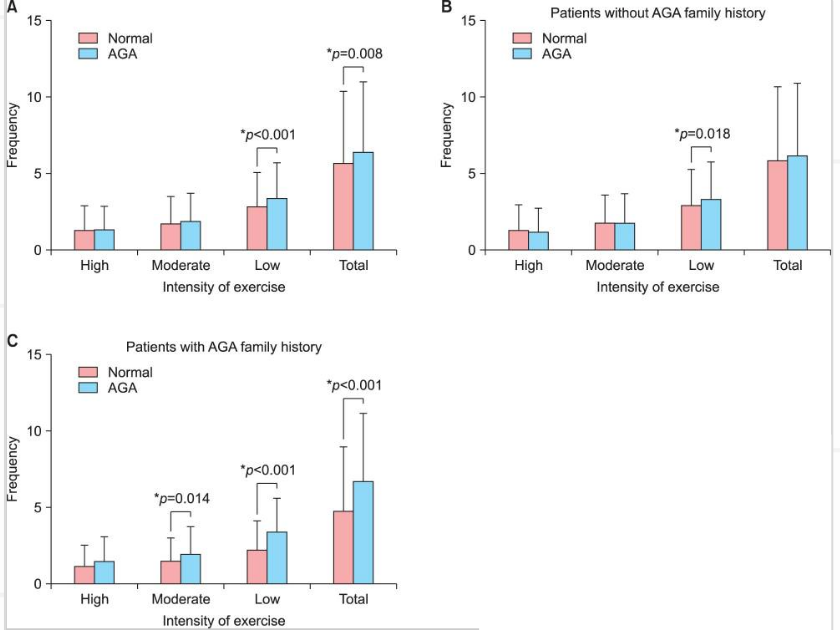

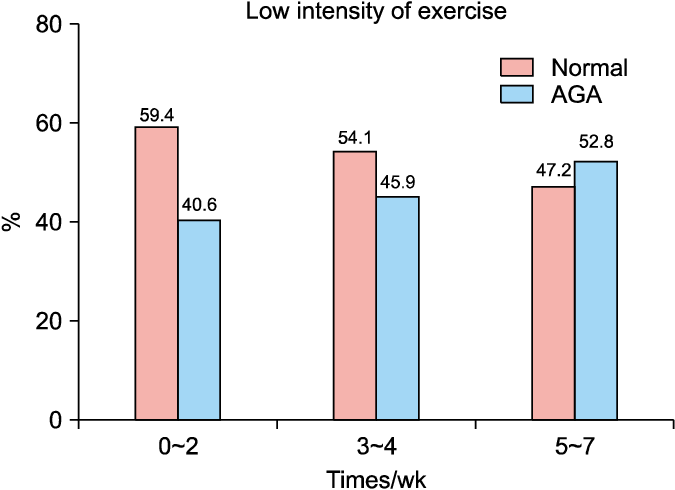

In 2017, a group of researchers issued a survey to over 1,110 patients with and without androgenic alopecia. They sought to answer one question: is there an association between androgenic alopecia and the frequency and/or intensity of exercise?[2]https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5500728/

Just like with the 2021 study, this research group observed no association between androgenic alopecia and high-intensity levels of exercise. However, after controlling for a familial history of hair loss, researchers found statistically significant associations between moderate- and low-intensity levels of exercise and androgenic alopecia.

What might explain these findings? The authors argued that androgenic alopecia is an innately inflammatory process. They also cited research implying that longer durations of exercise generate more reactive oxygen species (i.e., inflammation) within the body. As such, the researchers suggested that exercise might exacerbate inflammation in balding-prone regions, thus accelerating the balding process.

It’s another plausible argument – and one that (at face value) makes it harder to determine what to believe when it comes to exercise and its relationship to hair loss. But if we dig a bit deeper, we can start to get better answers.

What might explain the differences?

On the surface, the results of these studies appear to conflict. Just look at the overall findings: It isn’t until we dig deeper that we realize these studies are not totally comparable. Here’s why.

Reason #1: Both studies asked different questions

The 2021 study asked about the rate of progression of androgenic alopecia given a fixed six-month window of exercise habits. The 2017 study asked about the presence of androgenic alopecia given someone’s overall exercise habits.

Do you see the difference?

The 2021 study is asking research questions built around determining if exercise can influence changes to the progression of androgenic alopecia. The 2017 study is simply asking, based on someone’s exercise habits, whether they have androgenic alopecia.

Those are different questions! And based on our analysis of the data, the 2017 study is not designed adequately enough to actually determine if exercise habits have any relation to hair loss outside of the presence or absence of androgenic alopecia.

This brings us to our second point …

Reason #2: The 2017 study findings might have more to do with reverse causality than an actual connection between exercise and hair loss

“Reverse causality” is a term used to describe when a study’s findings of an association between two variables might imply causality, but not necessarily bidirectionally. Let’s give two examples:

- Researchers find an association between sunbathing and sunspots on the skin. Does sunbathing cause sunspots? Most likely. Do sunspots cause sunbathing? Probably not. In this case, reverse causality does not apply.

- Researchers find a link between smoking and depression. Does smoking cause depression? Mechanistically, many researchers believe smoking contributes to depression. But it’s also just as possible that depression can lead to unhealthy lifestyle habits – like smoking. In this case, reverse causality does apply.

Circling back to the findings of that 2017 study on exercise: does more low- and moderate-intensity exercise really increase the rate of pattern hair loss? Or is it that people are exercising more because they have hair loss? Evidence implicates the latter more than the former. Why? Because:

- Several studies have found that androgenic alopecia lowers self-perceptions of attractiveness and carries an immense psychological toll in those who are greatly affected – thus increasing rates of depression.

- Exercise is one tool (within our control) that can not only improve our appearance, but also lessen the severity of depression.

- That 2017 study only found a relationship between exercise and hair loss when controlling for a familial history of hair loss. In other words, the relationship only existed in subjects who had the expectation that they – like their parents – would also go bald.

Therefore, based on the findings of the 2017 study, we can just as effectively (and perhaps more effectively) argue that participants were exercising more as a means to counteract the psychological (and self-perceived physical) tolls of balding, than we can effectively argue that the exercise itself was causing a higher rate of balding.

For these reasons, we find the 2021 study to be a lot more powerful (and impactful) for hair loss sufferers, and probably closer to the truth (at least with the data so far).

Is There One Best Workout For Hair Growth?

Probably not. And to be clear: no one (including those 2021 study authors) is claiming that exercise of any form is a frontline therapeutic for androgenic alopecia.

But as an accelerator, certain lifestyle choices – like the absence of regular aerobic exercise – might act as a negative contributor to the balding process. And with possible beneficial effects from both a physical and psychological perspective, it probably doesn’t hurt to start building more exercise into our weekly routine.

So what’s the perfect workout for maintaining a healthy hormonal balance… and possibly staving off a faster progression of pattern hair loss? Well, the first thing to realize is that in the 2021 study mentioned above, there weren’t any exercises that appeared to be worsening hair loss outcomes. So, people shouldn’t rush to cancel HIIT workouts or weightlifting sessions – or substitute those for long cardio sessions – all for the sake of their hair.

Instead, hair loss sufferers might want to simply consider adding in manageable amounts of aerobic exercise into their exercise regimens. For some, that might mean adding light, 60-minute aerobic efforts 2-3 times weekly: swimming, jogging, fast-paced hikes, playing frisbee and/or soccer in parks with friends, you name it.

A good gauge is to exercise hard enough to sweat, but easy enough to maintain a conversation with the partner next to you. That’s it.

Remember, in the 2021 study, over 60 minutes of activity had a more positive influence on hair growth than “leisure activities,” and won’t trigger a stress response, which puts you at risk for increased inflammation.

Move more, enjoy the ride, and enjoy the fact that making these changes is not just for hair health, but primarily for a better healthspan, improved longevity, happiness, resilience to stress, and lower levels of anxiety. That should make the effort both fun and rewarding.

Summary

There’s conflicting evidence regarding the relationship between hair loss and exercise. The findings of at least one recent study point to the merit of long-duration aerobic workouts, while other studies seem to link androgenic alopecia with working out.

When we dig more deeply into exactly which questions were asked and what was measured in each study, the research isn’t as conflicting as it first seems. For this reason, we’d lean pro-exercise if you’re wondering about canceling your gym membership.

Exercise is not a frontline treatment for hair loss, but regular movement will positively influence your health and happiness. Plus, as an accelerator, lifestyle choices such as the absence of regular aerobic exercise might act as a negative contributor to the balding process.

Rob English is a researcher, medical editor, and the founder of perfecthairhealth.com. He acts as a peer reviewer for scholarly journals and has published five peer-reviewed papers on androgenic alopecia. He writes regularly about the science behind hair loss (and hair growth). Feel free to browse his long-form articles and publications throughout this site.