Biotin Supplements For Hair Loss: Helpful, Harmful, Or Neither?

Biotin is one of the most popular supplements in the hair loss community. If you’ve invested any time into researching hair loss, chances are you’ve stumbled upon information about biotin, biotin deficiencies, and claims about how this vitamin is critical to hair growth.

Back in 2007, when I was first diagnosed with male pattern hair loss, I came across this same information. And, like millions of other people, I inevitably started supplementing with biotin in hopes that it’d improve my hair.

I’ll save you the anticipation: biotin supplementation didn’t improve my hair loss.

In fact, evidence shows that biotin supplementation doesn’t improve hair growth for the overwhelming majority of people. For most hair loss sufferers in the developed world, biotin supplementation is useless. For a select few, it’s dangerous. And even for those with a biotin deficiency and hair loss, supplementation does not consistently improve hair growth.

This article is here to set the record straight on biotin-hair loss connection. We’ll uncover the evidence, reveal the best arguments for and against biotin, and then showcase the people most likely to see hair regrowth from supplementing.

Specifically, we’ll uncover:

- The details: What biotin is, what it does, and how this vitamin became so popular in the hair loss community.

- The evidence for biotin: the studies that manufacturers use to convince us that supplementation is necessary.

- The evidence against biotin: the studies showing that biotin supplementation is largely useless and unnecessary for the overwhelming majority of hair loss sufferers.

- The exceptions: the people who will see hair regrowth from biotin supplementation, and how to determine if you’re one of them.

By the end, we’ll have a firm understanding of what biotin is, its role in hair loss (and hair growth), and how this vitamin’s popularity is rooted more so in clever marketing than it is in sound science.

Summary

The strongest evidence supporting biotin supplementation for hair regrowth comes from studies on children with genetic mutations that result in severe biotin deficiencies. Biotin deficiencies of this severity are extremely rare in the general population.

Several studies show equivalent levels of biotin in both people with and without hair loss. Moreover, 50% of women will develop a biotin deficiency during pregnancy. Ironically, this period of time is also when women report increased hair thickness.

There are studies showing that biotin may improve hair loss. But in general, this is only true for people who are already biotin deficient. The prevalence of a biotin deficiency is debated; it varies wildly depending on the study you cite. But in general, only a small fraction of people have a biotin deficiency severe enough to contribute to hair thinning.

The people at the highest risk of severe biotin deficiencies are those who have genetic disorders, are alcoholics, heavy smokers, antibiotic abusers, use medications (like anti-convulstants or Accutane), and/or are pregnant.

Rather than spending money on biotin, a better investment of your time and energy is probably to (1) test for a biotin deficiency, (2) identify what form of hair loss you have, and (3) target your specific cause of hair loss with clinically-proven compounds, rather than guessing in the dark with vitamins and supplements.

What is biotin?

Biotin, also known as vitamin B7 (or vitamin H), is part of the B-complex family of vitamins. Biotin plays a key role in hundreds of bodily functions, and is considered essential to human health. In other words, we can’t function normally if we’re significantly deficient in this vitamin.

Where do we get biotin?

Our bodies acquire biotin through two main sources: (1) our gut bacteria, and (2) our food choices.

- Gut bacteria. Certain bacterial species found inside our gut – i.e., Bacteroides fragilis, Prevotella copri, Fusobacterium varium, and Campylobacter coli – produce biotin as a byproduct of their own digestion of our food particles. This biotin is then “reabsorbed” through transport chains inside our colons, and then redistributed throughout the body.

- Food. Biotin is found predominantly in animal products – specifically red meats, organ meats, eggs, and certain fish. But it’s also found in moderate degrees in nuts, avocados, and certain vegetables.

For U.S. adults, the recommended daily intake of biotin is 30 mcg daily. Studies have found that, in most developed countries, the average dietary intake of biotin is 35-75 mcg daily. This, in combination with the amount of biotin produced by our gut bacteria, is usually more than enough to meet all of our daily biotin needs.

What does biotin do?

Like most B vitamins, biotin is responsible for a myriad of functions. A few of the bigger roles that biotin plays:

- ATP production: Biotin plays a role in the production of ATP, the energy currency of the body. In other words, biotin helps us produce the energy our cells need to complete their functions.

- Epigenetics: Biotin assists in the process of epigenetic changes, whereby environmental inputs influence the way our genes instruct our cells to produce proteins.

- Liver and immune function: Over 2,000 genes in lymphoid and liver cells have been found to be dependent on biotin for their function.

So, it’s clear that biotin is essential for overall health. But is biotin essential to hair health?

The short answer: sort of… but not in the way most people are led to believe.

To illustrate this, we’ll build the strongest argument for why biotin is critical to hair health. This is the argument most biotin manufacturers will present when trying to sell you a supplement.

Then we’ll uncover data that contradicts this argument and introduces important nuance. In doing so, we’ll reveal why biotin supplementation is largely unnecessary for the overwhelming majority of hair loss sufferers.

The evidence supporting biotin supplementation for hair loss

If you ask any biotin manufacturer if biotin is important for hair health, the answer is almost always “yes”, and the justifications for why is usually the following argument:

- Biotin plays a role in the production of keratin – a protein that makes up the hair shaft.

- In vitro studies (i.e., tests done in petri dishes) show that when biotin is incubated with keratin-producing cells, biotin doesn’t increase the production of keratin proteins. However, when biotin is incubated with animal hair follicles, sufficient levels of biotin appear necessary for the maintenance of hair growth and the production of keratin-producing cells. Therefore, without biotin, evidence suggests that animal hair shafts don’t grow properly.

- In human studies, studies have linked biotin deficiencies to certain types of hair loss. Moreover, biotin deficiencies are often observed in female hair loss sufferers. And many case reports have shown that biotin supplementation can actually regrow hair in those with a biotin deficiency. (More on this later.)

In a vacuum, this makes biotin supplementation sound incredibly promising. When I first read that same information back in 2007, I bought into biotin’s importance, and I immediately started supplementing.

What I didn’t bother to do?

- Dig into the actual studies supporting biotin supplementation for hair growth in humans

- Learn about the participants inside those studies – who they were, their underlying conditions, etc.

- Compare their hair loss to mine, so that I could determine if biotin supplementation might make sense for me

If I’d done this exercise, I would’ve realized that the participants inside these studies are nothing like me, that biotin supplementation only helped them because of their unusual circumstances, and that I should’ve never (1) applied their situation to my own, (2) started supplementing with biotin, and (3) hoped for similar results.

To keep you from making my mistakes, we’ll go through these studies together. In doing so, we’ll reveal why these studies’ findings aren’t necessarily applicable to the overwhelming majority of people with hair loss. This way, you’ll be in a better position to determine if biotin supplementation might help you, harm you, or just waste your money.

The evidence against widespread biotin supplementation

A Review of the Use of Biotin for Hair Loss (Patel et al., 2017)

This 2017 literature review examined all of the available case reports showing a link between biotin supplementation and hair loss – 18 reports in total. In all 18 studies, each study participants had some degree of biotin deficiency. And in each report, biotin supplementation improved hair growth.

At face value, this is encouraging. If you only read the summary of this review, you’ll walk away with the belief that in the presence of a biotin deficiency, supplementation can help regrow hair.

Unfortunately, this summary doesn’t tell the full story. Why? Because when we take a closer look at the participants inside these case reports, we realize that most of them don’t represent the average hair loss sufferer. For example:

- 15/18 case reports were on patients with an underlying disease or genetic mutation that prevented them from absorbing dietary biotin.

- Of the 3/18 case reports where a biotin deficiency was present in the absence of a disease or genetic mutation, none of these patients had alopecia (i.e., hair loss).

- In 18/18 case reports, all participants were children under the age of six years old.

In other words, this review could only find evidence on biotin supplementation improving hair loss in children, and more specifically, children with rare genetic mutations and/or diseases that caused their biotin deficiency in the first place.

Therefore, the evidence in this review cannot be applied to modern-day adults who are losing their hair. Yet ironically, this literature review is what supplement manufacturers reference in their marketing materials to try to get adults with hair loss to buy biotin.

But what about adults with hair loss? Is there any evidence that this group might disproportionately suffer from a biotin deficiency, and that biotin supplementation might improve their health and their hair?

There are a few studied that have attempted to answer this. We’ll walk through them below.

Serum Biotin Levels in Women Complaining of Hair Loss (Trüeb, 2016)

Ralph Trüeb, one of the most prolific hair loss researchers of the 21st century, conducted a study to determine just how many women with self-perceived hair loss also had a biotin deficiency. The study was robust: 541 women were included in his study. And the results were surprising.

Of all females complaining of hair loss, 38% of them had a biotin deficiency. That’s a high number, and it lends credence to the idea that maybe a large percentage of women dealing with hair loss should start supplementing with biotin.

That is, until we look more closely at the study details:

1. Nearly two-thirds of the women in this study did not have a biotin deficiency.

In other words, 62% of women with hair loss in this study had, at a minimum, normal biotin levels. Moreover, 13% of these women had optimal biotin levels… suggesting that hair loss can occur even without a biotin deficiency.

2. Many women with a biotin deficiency had a health history that increased their risk of deficiency.

Of the women complaining of hair loss who also had a biotin deficiency, 11% of them had health factors that greatly elevated their risk of developing a deficiency in the first place. This included medication use, antibiotic use, genetic mutations, and more (more on this later).

3. Of the women who underwent scalp examinations, hair loss was detected in the same percentage of women with and without a biotin deficiency.

This study was done on a group of “women complaining of hair loss” – or in other words, women with self-perceived hair thinning. Therefore, one part of this study was to give a scalp examination to a subset of these women to determine if they actually had detectable markers for hair thinning, or a diagnosable hair loss disorder.

So, a subset of the women underwent what’s known as a trichogram. A trichogram is a lens-like device that zooms in on the scalp to magnify the skin and hair. This is to determine hair shaft characteristics, the percentage of hairs in their growth versus resting stages, the presence of dermatitis (scalp flakiness), and more.

These devices are used as tools to help diagnose someone’s type of hair loss. For instance, one of the most common causes of hair loss in adult women is telogen effluvium. This is characterized by a high number of hairs in the shedding versus growth phase of the hair cycle. A trichogram helps to calculate these ratios, and thereby diagnose this specific hair loss disorder.

Interestingly, in this study, a trichogram examination was conducted on both a subgroup of females with optimal biotin levels and a group of women with a biotin deficiency. The findings?

- Of those with optimal biotin levels, 24% of them had telogen effluvium

- Of those with a biotin deficiency, 24% of them had telogen effluvium

In other words, for the women with self-perceived hair loss, those with optimal biotin levels and deficient biotin levels had the exact same percentage rate of a diagnosable hair loss disorder: 24%. For the rest of these women, no diagnosable hair loss disorder was present.

The authors of this study suggested that these results might indicate that a trichogram is not a sensitive- or specific-enough test for diagnosing mild hair loss from a biotin deficiency. At the same time, we could also interpret these results to suggest that hair loss severe enough to meet a diagnosis criteria occurs in equal rates for both women with poor biotin levels and women with optimal biotin status.

If true, that would suggest that a biotin deficiency has very little relevance to most women with hair loss overall, and that the presence of a deficiency (in the overwhelming majority of cases) might just be coincidental.

In fact, this secondary interpretation seems more closely aligned with the study’s conclusions, which state:

The custom of treating women complaining of hair loss in an indiscriminate manner with oral biotin supplementation is to be rejected unless biotin deficiency and its significance for the complaint of hair loss in an individual has been demonstrated. It must be kept in mind that hair loss in women may be of multifactorial origin, including female androgenetic alopecia, other nutritional deficiencies (e.g., iron deficiency), and/or endocrine disorders (e.g., thyroid disorder). Treating the patient exclusively with oral biotin poses the risk of neglect or delay of appropriate treatment of hair loss in the particular case.

Long-story short: Trüeb’s study concludes that for most women dealing with hair loss, (1) biotin supplementation is largely unnecessary, (2) it’s only warranted in women with a biotin deficiency, and (3) even if the biotin deficiency overlaps with hair loss, it’s still unclear whether supplementation will actually improve that hair loss, because (4) female hair loss is multifactorial.

This is all helpful information, and clarifies that biotin supplementation certainly isn’t warranted for everyone. But what if we expand our test group beyond women with self-perceived hair loss and look at both men and women with diagnosable hair loss? Do we have any studies determining if biotin deficiencies are present, if biotin supplementation is warranted, and if biotin might help with hair regrowth?

Yes.

Biotin Deficiency in Telogen Effluvium: Fact or Fiction? (Mohammed et al., 2020)

Earlier this year, a group of researchers wanted to determine if there biotin deficiencies were more common in men and women with telogen effluvium compared to the general population. So, they set up a case-control study to uncover the answers – which included 80 participants with diagnosed telogen effluvium, and 20 people without hair loss for the control group.

The results:

- All participants in the study – including those with hair loss – had optimal biotin levels.

- There were no statistical differences in biotin levels between men and women with telogen effluvium and the control group (i.e., those without hair loss).

In other words, biotin levels didn’t differ between those with hair loss and those without hair loss. To summarize the investigation team’s conclusions:

According to our study, biotin deficiency is rare and its serum levels showed no significant difference between cases and control subjects… This study also stands against prescribing biotin supplements to all cases of hair loss without a confirmed biotin deficiency, as it might expose certain people to potential harm.

This means that there is no verifiable evidence that biotin supplementation leads to hair regrowth outside of patients with a biotin deficiency. The body of literature simply doesn’t support it. This is also why the general consensus, among experts, is that high-dose biotin supplementation should be rejected as a treatment for hair loss… unless a deficiency is confirmed.

But, there are a few more questions we need to ask before ruling out biotin supplementation for the majority of hair loss sufferers:

- How common is a biotin deficiency?

- Is it common enough that it might be a prevailing cause of hair loss for a majority of people?

- Is it common enough that the average hair loss sufferer should consider testing for a deficiency?

In doing so, we’ll begin to get a better idea of who might actually benefit from supplementation.

How common is a biotin deficiency in the developed world?

It’s debated, mainly because the answer depends on the country you’re examining, the population you’re examining, and the line you decide to draw for what is considered a deficiency.

For example, Trüeb’s study found that 38% of women complaining of hair loss had a biotin deficiency. Contrast this to Mohammed’s study, which found that 0% of participants with and without hair loss had a biotin deficiency.

Trüeb’s study was done in Switzerland; Mohammed’s study was done in Egypt. Trüeb’s study was done on women; Mohammed’s study was done on men and women.

But what about people in the U.K. or America? How many of them have a biotin deficiency?

It’s tough to say. Broadly speaking, this 2012 CDC report suggests that fewer than 10% of Americans have a nutrient deficiency. So, if we choose to believe this data, we can presume that fewer than 10% of Americans would also have a biotin deficiency. (Note: I don’t trust this data, as studies have also found that 42% of Americans are vitamin D deficient).

Based on the studies available, it seems reasonable to assume that the prevalence of biotin deficiencies are (1) relatively higher among women, but (2) still low overall for both men and women in the general population. Moreover, this position seems to be supported by data. To reiterate from earlier:

- The recommended daily intake for biotin is 30 mcg daily.

- People in developed nations consume 35-70 mcg daily of biotin from their diets.

- This intake doesn’t factor in the amount of biotin also endogenously produced by gut bacteria.

Therefore, in developed nations, most people should be getting more than enough biotin.

So, who is at risk of a biotin deficiency?

There are cases where biotin deficiencies occur… even with adequate dietary biotin intake.

If you’re dealing with hair loss and you meet any of the following qualifiers, you may want to test biotin levels to see if supplementation might help improve things

Risk factors for a biotin deficiency (beyond a poor diet)

- A genetic deficiency in the biotinidase enzyme. This is where a genetic mutation results in your lack of an enzyme needed to break down biotin. The consequence? An impaired ability to absorb biotin from food. This deficiency can be partial or profound, with profound deficiency leading to more severe biotin deficiency than partial. The incidence of partial deficiency is rare – about 1 in 110,000. Profound deficiency is even rarer, affecting 1 in about 140,000. This deficiency is more common among Hispanics and less common among African Americans. Individuals with a true biotinidase deficiency will require lifelong supplementation with biotin to prevent a myriad of health problems from cropping up, including hair loss.

- Alcohol abuse. Alcoholics are more likely to present with low biotin levels than those who don’t abuse alcohol.

- Antibiotic abuse. Antibiotics may contribute to gut dysbiosis which can dampen biotin production by gut microbiota. At the same time, antibiotic-induced dysbiosis can really only induce biotin deficiency in the absence of biotin consumption. Thus, antibiotic-induced biotin deficiency is likely still extremely rare.

- Medication use. Anticonvulsant therapy is known to enhance biotin catabolism, which may increase the risk of biotin deficiency.

- Parenteral nutrition. Low levels of biotin have been reported in patients receiving parenteral nutrition. This is when people can no longer eat by way of chewing and swallowing foods, so they are given feeding tubes or vitamins + nutrients intravenously to meet caloric and nutritional demands.

- Smoking. Smoking, like anticonvulsants, enhances biotin breakdown, increasing the risk of a deficiency.

- Accutane use. Accutane decreases biotinidase activity, thereby making it more difficult to obtain adequate biotin from food alone.

- Gastrointestinal disease. Gastrointestinal issues can impair biotin absorption (and nutrient absorption overall), which may lead to biotin deficiency.

- Pregnancy. About half of the pregnant women in the U.S. have suboptimal biotin levels, which is why biotin supplementation is almost always recommended as a standard for prenatal care.

In cases where you have hair loss and at least one of these risk factors, it might be worth testing your biotin levels.

The people most likely to benefit from biotin supplementation: those with a biotinidase deficiency

When we look back at the 18 case reports demonstrating benefit with biotin supplementation, we see that the majority of them were patients with an inherited biotinidase deficiency. They were also children under the age of 6.

This isn’t to say that adults with a biotinidase deficiency and hair loss won’t benefit from biotin supplementation. Rather, it’s just interesting that the strongest evidence supporting biotin supplementation for hair growth is in studies on children with rare genetic mutations, rather than adults with general hair thinning.

That said, it is not surprising that a majority of the evidence is comprised of people with this condition. With a biotinidase deficiency, someone’s biotin levels can drop to nearly zero… and for their entire lives. And, as with most deficiencies, the most dramatic effects (i.e., hair loss) are generally seen in the extremes of that deficiency rather than milder, more prevalent cases occasionally observed in the general population.

Outside of this, the only other study demonstrating hair-related benefits from supplementing during a biotin deficiency was on children taking antiepileptics. These children had experienced hair loss following the administration of valproic acid. While the investigators found no evidence of decreased biotin levels or a biotinidase deficiency, they did note an improvement in hair loss with biotin supplementation at 10mg per day.

Lastly, while pregnant women appear to be at a relevant risk of biotin deficiency, there is currently no evidence that biotin deficiency in pregnancy can cause hair loss. In fact, most women report an increase in hair density during pregnancy… even despite biotin deficiencies being so widespread during this period.

| Those likely to benefit or require a biotin supplement | Those who might be at risk of biotin deficiency, but may get enough dietary biotin to counter the risk of deficiency | Those not at risk of biotin deficiency attributed to hair loss, who likely won’t benefit from biotin supplementation |

| Individuals with genetically-inherited biotinidase deficiencies | Alcoholics, smokers, and/or antibiotic abusers | The general hair loss population |

| Individuals taking epileptics who also have hair loss | Accutane users | Individuals wanting to speed up the growth of their hair |

| Patients receiving parenteral nutrition | ||

| Patients with gastrointestinal disease |

The bottom line: outside of rare genetic mutations, biotin is unlikely to confer any benefit to the overwhelming majority of hair loss sufferers.

How do I find out if I have a biotinidase deficiency?

Most people are diagnosed with a biotinidase deficiency at birth. If not, they are usually diagnosed early into childhood – when the more serious symptoms begin to express themselves. As such, most people with biotinidase deficiency will already know it – and will likely already be supplementing with biotin.

Is biotin supplementation ever dangerous?

For the most part, no. Biotin is water-soluble, making it very difficult to overdose – as any unused biotin is generally excreted as waste product rather than stored in other tissues.

Having said that, excessive biotin supplementation is not absent of concerns. In fact, there are a few cases where biotin supplementation has indirectly caused fatalities.

For instance, biotin supplementation has been frequently reported to interfere with lab testing, specifically lab tests for (1) thyroid function, and (2) troponin, a protein used to diagnose a heart attack. As a result, testing your thyroid hormones or diagnosing a heart attack using a troponin assay while taking biotin can result in a false test result. More specifically, it can falsely elevate your thyroid hormones and produce an incorrect troponin level.

The ramifications of this are two-fold: (1) a hypothyroid condition may be misdiagnosed either as normal or hyperthyroid and (2) a falsely low troponin test may cause a heart attack to go undiagnosed, potentially leading to death (this has happened at least once before).

The bottom line: unless you’re…

- A severely malnourished child / adult, or…

- Have a genetic mutation or chronic disease interfering with biotin absorption, or…

- Have a history of alcoholism and/or antibiotic abuse…

…then it’s highly unlikely that you have a biotin deficiency that is severe enough to cause hair loss. This means that for the overwhelming majority of us, biotin supplementation for hair growth is more or less useless.

If I’m deficient in biotin and dealing with hair loss, how can I tell if biotin supplementation might benefit me?

If you’re dealing with a biotin deficiency and hair loss, then supplementation is warranted… and in some cases, it might even help. However, supplementation’s helpfulness really depends on the severity of your biotin deficiency.

Earlier, we mentioned how biotin supplements only seem to regrow hair in cases of severe deficiencies – like that of a biotinidase deficiency. Well, interestingly enough, there are symptoms of severe biotin deficiencies that can help you gauge whether supplementation might also help your hair loss.

Revisiting Trüeb’s study, there was another finding we left unmentioned. Of the women with a biotin deficiency + self-perceived hair loss, 35% of them had a scalp condition called seborrheic dermatitis. Of the women with optimum biotin levels + self-perceived hair loss, 0% had seborrheic dermatitis.

This suggests that seborrheic-like dermatitis is significantly more common in biotin-deficient individuals with hair loss than those without biotin deficiency and hair loss.

Not surprisingly, biotin deficiency may be a driver of seborrheic dermatitis. In fact, biotin along with other B-complex vitamins have been used to treat this very condition, with the first evidence of its effectiveness dating back to 1972.

As such, it’s possible that multiple symptoms of biotin deficiency – like seborrheic dermatitis plus hair loss – are a better predictor of biotin deficiency-related hair loss than just having a biotin deficiency and hair loss alone.

So, if you have seborrheic dermatitis, hair loss, and you suspect a biotin deficiency – there might be a higher chance that your biotin deficiency is severe enough to cause hair loss. And in that case, biotin supplementation should help.

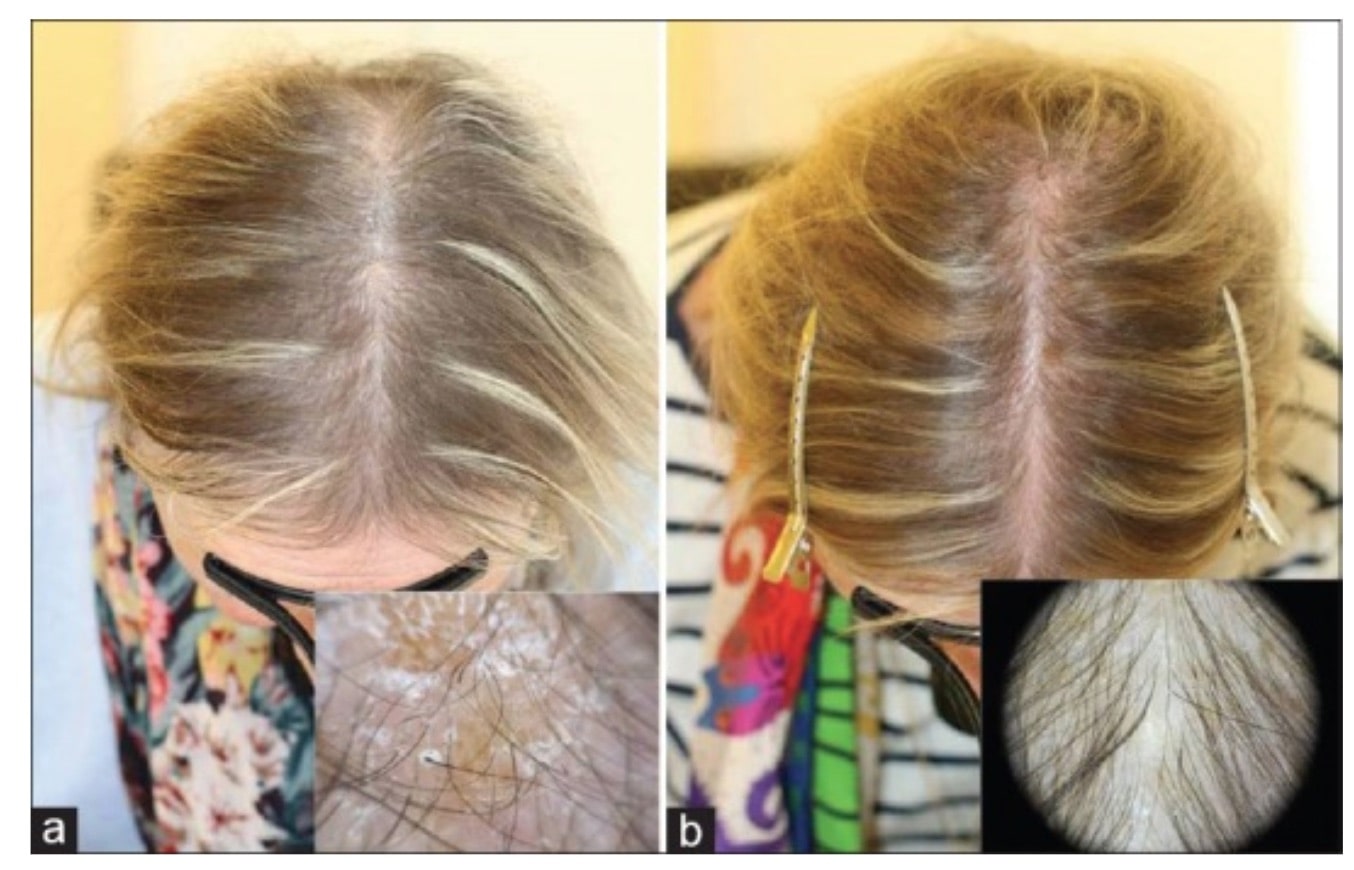

In fact, here’s a photo from Trüeb’s study showing the effects of biotin supplementation on a female who fit this exact criteria:

Biotin deficiency + hair loss + seborrheic dermatitis: progress after 3 months of biotin (5mg/day)

The verdict on biotin

Biotin supplementation is widespread among hair loss sufferers, but it’s only warranted in a small percentage of cases.

In general, studies show no differences in biotin levels for people with and without hair loss. While one study found that 38% of women with self-perceived hair loss had a biotin deficiency, that study also showed equal percentages of women with diagnosable hair loss in both the biotin-deficient and biotin-optimum groups. Moreover, for men and women with moderate biotin deficiencies, it’s still unclear if supplementation will improve their hair (if at all).

The best evidence for biotin supplementation causing hair regrowth comes from case reports of people with a biotinidase deficiency. These reports are on children under the age of six who have severe biotin deficiencies. These studies are not applicable to most adult hair loss sufferers.

If you have hair loss and your diet, lifestyle, medications, or genetic profile puts you at risk of a biotin deficiency, then it’s worth testing your biotin levels to see if supplementation might help. If you’re deficient, supplementation might be warranted. And if you have hair loss + seborrheic dermatitis + a biotin deficiency, the odds are better that you’ll see an improvement.

The bottom line: invest your money into determining your own causes of hair loss rather than blindly supplementing. That way, you can more effectively target your unique drivers of hair loss, rather than waste money on well-marketed but (mostly) scientifically baseless supplements.

Rob English is a researcher, medical editor, and the founder of perfecthairhealth.com. He acts as a peer reviewer for scholarly journals and has published five peer-reviewed papers on androgenic alopecia. He writes regularly about the science behind hair loss (and hair growth). Feel free to browse his long-form articles and publications throughout this site.

Hi Rob,

i have a general question to your hair loss program: Does your hair loss program have any solutions for Gut infection causing hair loss?

Hey Aslan,

The membership site includes a lot of information about gut health, its relationship to a variety of hair loss disorders, and which steps you can take (based on clinical data) to improve your gut as a means to potentially improve your hair loss.

Best,

Rob

Thank you!

Of course! I’m happy to answer any other questions as well.

Hi Rob! Thank you for this article! I was wondering if during your studies you have stumbled on the nettle oil and its effect on the hair loss when used as a topical on the scalp. I would appreciate your opinion on that. Thank you!!

Hey Holta,

Thanks for reaching out. There’s some evidence that stinging nettle has anti-inflammatory properties, as it can reduce the expression of a pro-inflammatory signaling protein known as nuclear factor kappa beta-1. There’s also some evidence that stinging nettle may help DHT levels, as the plant contains beta sitosterol (which likely helps reduce 5-alpha reductase activity – the same enzyme that converts testosterone into DHT). So, you could point to that evidence and say that because stinging nettle helps reduce inflammation + lower DHT, it probably will help with pattern hair loss.

At the same time, the evidence supporting those claims comes from cell culture studies and mouse models. So, there’s really not much data available to answer your question.

Moreover, many of the volatile acids inside herbal extracts have short half lives. This means that while they might help lower inflammation and/or reduce DHT, they only do so for a relatively short time period (at least compared to something like finasteride). This means usage frequencies for natural topicals need to increase – with applications 2-4x daily to see significant effects. At that rate, natural topicals become pretty expensive. So, if you’re thinking of using stinging nettle, you may want to consider this.

Long-story short: stinging nettle might help a little, but there’s not enough evidence to confirm this. In any case, I probably wouldn’t rely exclusively on stinging nettle as a hair growth agent. Rather, I’d also want to combine it with other things.

Best,

Rob

Hi Rob, hope you are going great.

Hey I was wondering if you have any thoughts on whether muscle atrophy from being hypothyroid might contribute to scalp tension?

If the muscles around the perimeter of the scalp were to shrink at all via being hypo, this could cause them to pull the galea tighter due to their shorter length.

Any thoughts?

Hey Jasper,

It’s nice to hear from you. Great question.

To my understanding, muscular atrophy would actually reduce muscle tension in these tissues (that’s part of how Botox works; it immobilizes the muscle so that it cannot be used, which leads to atrophy over time). The only scenario where this wouldn’t be the case is if the atrophying muscle was also actively contracting and at significantly more force than before its atrophy. But that scenario feels a little unlikely for those with hypothyroidism.

I hope this helps!

Best,

Rob

Hey Rob!

I started doing the detumescence therapy from 2016 video and I have some questions for you:

1. Is it normal to lose between 30-50 hairs per session? I have noticed that I’ve lost a little bit of density but I’m not sure because I haven’t cut my hair since January because I want long hair, and even longer hair seem thinner.

2. Is there a big difference between 2016 techniques and the actual ones? It will work for me if I continue with the old one?

3. If my temples have receded a bit, also my crown and I’ve lost density in general on the top of my scalp, is this an AGA or it is a type of diffuse thinning? For me the most noticeable thing is the lost of density (on the top, not on the sides). Is like if the hair on the top was “dead” or with “no life”, and the sides and the back are full of wavy/curly hair.

4. What do you think about brushing with a wooden brush, like Dmitry Tamoikin’s technique?

Thank you Rob, you’re doing a great job!

Hey Arthur,

Thanks for reaching out. To answer your questions–

1. It depends on your starting hair density. In general, 50+ hairs feels a little high… although if you’ve got great hair density and normally shed 200+ hairs daily in the absence of AGA, then this isn’t necessarily problematic.

2. You can absolutely continue with the old techniques if you’d like. These older techniques are the ones that we investigated in our 2016 study – which found a response rate of ~75% for those committing 8+ months or longer. The new techniques are bit more refined and updated based on the learnings from that study. They’re only available inside our membership, and while I’d love for you to join so that we can interact more and connect one-on-one (or through the forums), I have zero interest in pressuring anybody to become members who don’t want to, or are already seeing success with the free materials.

3. This sounds like AGA, but it may be a combination of both AGA + telogen effluvium. To gain better insights into that determination, we’d need to have a longer-form discussion to learn more about the type of hairs you are shedding, the presence of miniaturization, your health history, etc.

4. I think they work great for some people! We actually have an Alternative Massage Technique video inside the membership, too – which covers these types of exercises. One of our members (Jenna) saw really impressive improvements with a bamboo brush. But they’re great so long as they don’t evoke excessive shedding.

I hope this helps!

Best,

Rob

Hello Rob (and everyone),

Thanks for the article, somehow I can relate. Never tested for biotine levels, but have seborrheic dermatitis and some poor digestion (gut). The doctor said that, in the meals, “I eat problems with the food” (stress).

Suplements I take include biotin, but it’s when I use shampoos with biotin that I notice improvement. Thing is, when they finish, they take along all hair I gained during the process.

Don’t know if it will help, oreven if you’d agree shampoos can have that effect but thought i’d share the experience. And by the way, massaging and seborrheic dermatitis don’t get along… feels like it increases seborrheic dermatitis and weakens the hair, shedding like there is no tomorrow.